Deutschendorf Origin Story

Deutschendorf is a family name with deep Prussian roots.

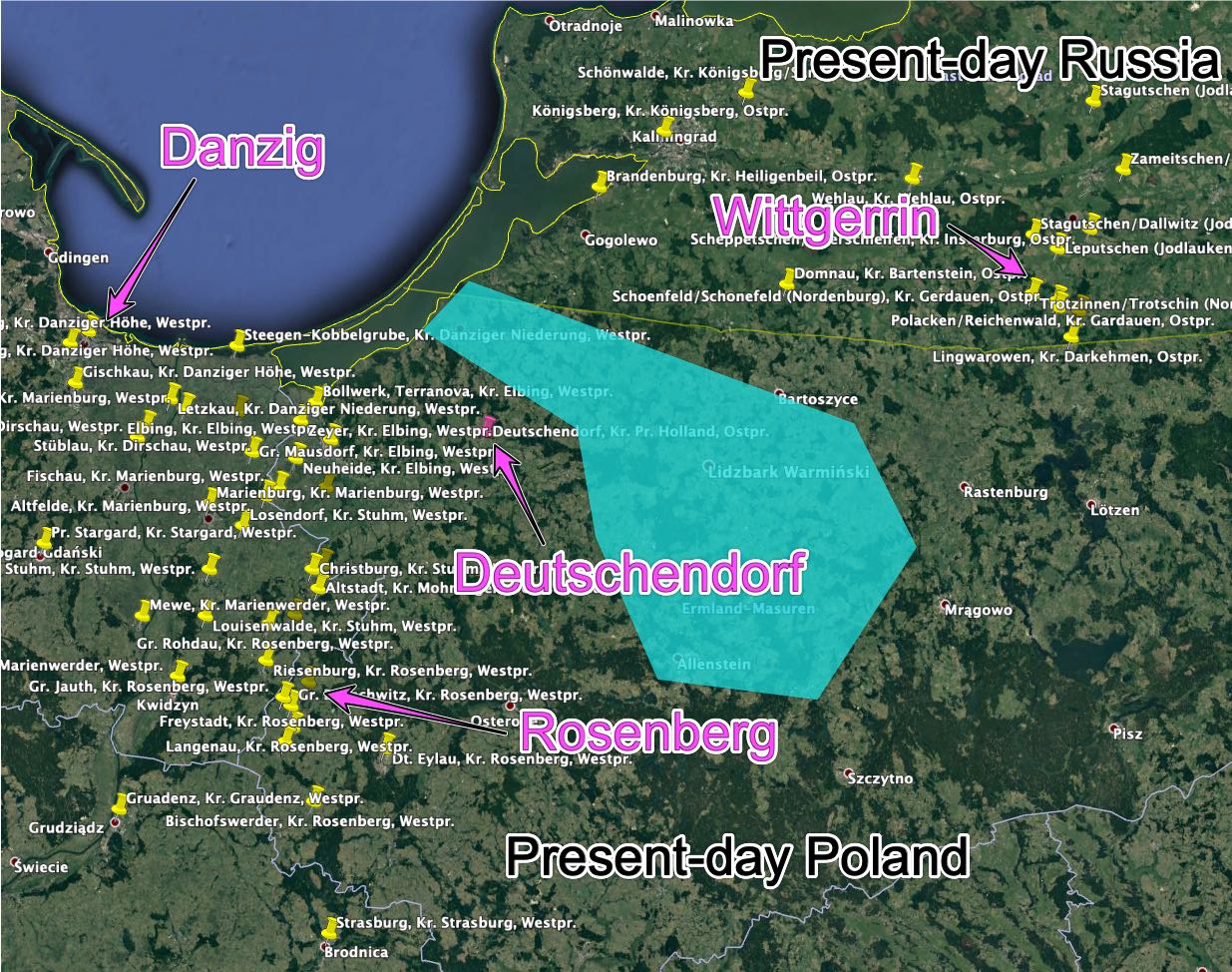

How do I know that? Well, if you search for references to the name "Deutschendorf" before the year 1850 on Ancestry.com – which has an excellent searchable database of old German church records – you won't find any references to Deutschendorfs living "Im Reich" (that is, in the German Reich to the west), but you will find dozens of references to Deutschendorfs living to the east in Prussia.

And more importantly, it turns out there was an East Prussian village founded by German settlers in the early 14th century called Deutschendorf, which is German for "German Village". Ironically, what was once the very German village of Deutschendorf, is today the small Polish town of Wilczęta, Poland.

In the map of Prussia above, the single pink pin is the former location of the village of Deutschendorf. Each yellow pin represents a town where I found old Protestant church records referencing at least one individual with the family name of Deutschendorf at any time before 1850. Clearly, the Deutschendorf family name was historically concentrated exclusively in Prussia.

The blue patch was a sub-region of East Prussia called Ermland which remained catholic after the Reformation. The first Protestant church wasn't founded there until 1792 (in Bischofsberg – Osptreußen: Biogrophie einer Provinz). Since the Deutschendorfs were Protestants, it's no surprise that we don't find any of them in Ermland.

At first, it seemed a little curious that I couldn't found a single church record referencing individuals named Deutschendorf in the direct vicinity of the village of Deutschendorf… the closest yellow pins are a couple dozen miles away.

I considered a few different explanations for this pattern of "Deutschendorf Distribution" – including political boundaries over the centuries, or perhaps even the potential wide-spread destruction of old church records during WWII. But none of those potential explanations fit the data very well.

Finally, I realized the most likely explanation: This pattern of "Deutschendorf Distribution" is best explained by the dialect those Deutschendorfs must have spoken. Namely, "Niederpreußisch" or "Low Prussian". So-called because the speech in this area was strongly influenced by the "Low German" dialects of Northern Germany (from the Lower Saxony region, among others).

Note that the map of Nieder- vs Hoch-Preußisch (Low- vs High-Prussian) perfectly matches the "Deutschendorf Distribution" pattern.

Anyhow, it seems clear that my family, as well as all other Deutschendorfs across the globe (including country singer John Denver), can trace their family histories to this East Prussian village of Deutschendorf. Unfortunately, there are some seemingly insurmountable hurdles to tracing that family heritage all too closely.

Village of Deutschendorf

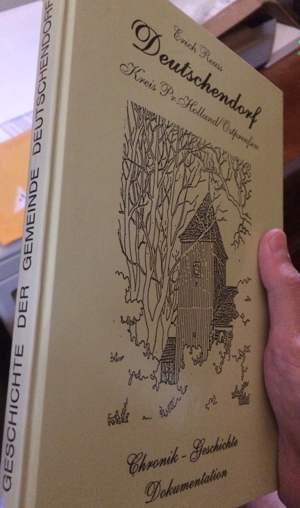

In 1993, a German genealogy enthusiast named Erich Reuss who also has ancestral ties to the town wrote a short book – a "Chronicle/History" – about the lost village of Deutschendorf. It wasn't easy to find, but I was able to acquire a copy online. If you want to purchase a copy, I would try the publisher first, although they never responded to my email requests.

According to Reuss' book, all historical records from Deutschendorf's Protestant church were lost in a fire after WWII. And indeed, no historical Deutschendorf church records are available on any online platform that I can find. So tracing any family's history explicitly back to the village of Deutschendorf via written church records seems literally impossible.

Reuss' book begins with a foreword which contains a fascinating and charming recounting of the origin of the village Deutschendorf, which I've translated and included directly below:

Although the existence of a church- or village-chronicle of Deutschendorf can be doubted, what cannot be doubted is that the Deutschendorf church books, which were lost to fire in 1945, contained much valuable information which is unfortunately no longer available to us.

The final "First Teacher" (»Erste Lehrer«) from Deutschendorf, Friedrich Konrad, wrote the following after the post-WWII German expulsion from Poland, under the date February 21, 1949:

After the horrible World War II, we German expellees find ourselves dispersed across all corners of what remains of our Fatherland. In our thoughts, we still think often about our beloved Homeland and we are loathe to give up some small hope that we may one day see it again. From here in the distance, the beauty of our Homeland, our lovely East Prussia, our Oberland (one name for the region in which Deutschendorf was located), and our home town of "Deutschendorf" is recalled all the more easily. Deutschendorf, you stood over 600 years, with your honorable Church. Over your founding, the Chronist reported the following:

The Teutonic Order followed the Pope's call and came to the old Prussian lands to settle there, and to spread Christianity. As the Teutonic Order conquered each area, they built there fortresses that were ruled by a Governor (»Komtur«).

The Governor of the Fortress Schwetz (a town in Prussia not too far from the eventual site of Deutschendorf), Heinrich von Gera, was once visiting in the West in the Town of Nebra (a town in Saxony). There he met another man named Heinrich - a Protestant preacher named Heinrich von Haesler who was there tasked with spreading the Word of God, and to say prayer at meals. He had spoken often to the preacher and described to him the beauty of the far-away Prussian lands.

One time Heinrich von Gera said to Heinrich the preacher: "Come back with me to Prussia!" But Heinrich von Haesler declined the invitation with the following reasoning: "But what shall I do there? I cannot wield a sword, nor can I plough or sow, so what use would I be there on the frontier?" Heinrich von Gera replied: "You can spread the Word of God!" After much consideration, the preacher Heinrich von Haesler agreed to relocate to Prussia with him.

And Heinrich of Gera now recruited many farmers (peasants) and hand-workers that wished to move with them. The farmers equipped their wagons, packed their most necessary belongings and provisions, set their women and children on the wagons, and began the long trek to the East. Along the way, as they camped overnight, they positioned their wagons in a circle as a sort of wagon-fortress with the towing-bars facing inward. In the middle, they made a fire to keep wild animals at bay.

After many struggles, they arrived at the Vistula river (in modern day Poland) where they stopped for a while; because the necessary bridges did not exist; the wagons had to be tediously transported across one at a time. After everything had made the crossing, they continued further east.

Soon, they were greeted by the towers of the great fortress of the Teutonic Order at Malbork Castle (a huge medieval castle that still stands and is a major tourist attraction in Poland) on the River Nogat.

They then made a longer stop at a further fortified town of the Teutonic Order, Elbing. Ships stood on the river Elbing, from which the travelers received herring, salt, and hand-tools, e.g. saws and axes and such. From the town they received meal and grain.

Soon they came upon a small stream, which was later named the »Niemandsgraben«, (No-man's-grave). There, the leader, Heinrich from Gera said, "Here shall be your new Homeland. Here we shall build a village (»Dorf«)."

The work began immediately. The forest was rooted out and cleared, the land was sowed, and wooden houses were built.

A wooden church was built in the middle of the village, but it burned down a couple of years later. A church of stone was built in its place, which was the eastern part (alter room) of the church which still stands today. The western part was built later, and the wooden tower yet later still.

(This website has two pictures of the church in Deutschendorf.)

As most of the village was finished, with most of the houses built of wood and covered with reeds or straw, Heinrich von Gera spoke to the preacher Heinrich von Haesler: "Now we must give the village a name. You are a learned man; name the village after a great and famous man!" Heinrich von Haesler responded: "The village shall not be named after a famous man. We are all Germans (»Deutsche«), therefore the village shall be named Deutschendorf (German Village)!"

The year of the village's founding is not precisely known, but lies between 1309 and 1311.

The village was provided with 80 »Hufen« (A »Huf« is an old German measurement equivalent to anywhere between 7.5 to 20 hectacres – that is, 750 to 2000 acres. So the village was given up to 160,000 acres in total.). The preacher, mayor and local smith were each given 4 »Hufen« (up to 80 acres),

The peasant farmers, however, were not free, but rather had to perform manual farm labor for the local land owner in nearby Karwinden; they were required to take their beasts of burden to Karwinden two or three times a week to perform farm work. If a peasant didn't stay on the land owner's good side, he would be chased off his own parcel of land which would then be given to another peasant farmer. The farmer's daughters could not marry without the approval of the local land owner. Only in much later times would these inherited conditions be lifted.

A courthouse was built in Deutschendorf, in which court days would be held for the surrounding region. Those convicted of serious crimes were sentenced to hanging on the gallows which stood on a nearby hill (»Galgenberg«).

Over the centuries, Deutschendorf developed into one of the largest villages in the county of »Preußisch Holland« (Prussian Holland – the county in which Deutschendorf was located. So called because many Dutch settlers were relocated there to help build canals and dykes and such. But AFAICT, our direct ancestors are more likely to have been among the German settlers – maybe even the ones described here – than the Dutch settlers.).

Deutschendorf was divided down the middle into an "Upper-" and "Lower-End" by a street which was later widened into a highway.

One of the farmers' parcels was vacated and used to build a few buildings for the settlers as well as some hand-workers and tenants. Thus was created a part of town known as the "Colony" (»Kolonie«).

Some of the farmers' parcels were quite far from the center of town. To make things easier, they built their homes and businesses on their own distant lands. Thus was created a part of town known as the "Outback" (»Abbauten«). Thus was the town divided into Upper-End, the Lower-End, the Colony and the Outback.

Each farmer's parcel also included a woods; the parts of which lay in the "Beech Wood", the "Oak Wood", the "Farmer's Wood", and the "Curvy Spot Wood" (»Krümmstuck«).

In the village lay larger ponds, that also aided in extinguishing fires. On the Lower-End, it was the "Street Pond" and the "Smith's Pond", on the Upper-End it was the "Shit? Pond" and the "Street Pond". Just outside the town (Richard Hinz) lay the "Sprindt(?) Pond", and in the woods, the "Curvy Spot Pond" which were both later emptied.

There are reports of a school being built around the end of the 18th Century, in which a hand-worker taught the children reading, writing and religion. Not until the following century were dedicated, educated teachers hired. The schoolhouse, which still stands today, was built in 1872; it contains two classrooms and living quarters for two teachers.

After the Protestant Reformation, the church was converted to a Protestant church. The "Confession Stool" near the altar still reminds one of the church's Catholic history. The organ was built in 1776. The massive "residence of the local preacher" (»Pfarrhaus«) fell victim to war after 200 years of existence.

The farmers' homes, which were still built in the style of the front-arbor-homes of Oberland (»Oberländer Vorlaubenhäuser«), and covered with reeds or straw, eventually gave way to stone homes without front arbors. The last »Vorlaubenhaus« across from the church (Paul Kunkel), was removed in the year 1929.

With the arrival of the Russians at the end of January 1945, Deutschendorf suffered so badly that it is hardly recognizable. Although the Homeland may lay in ruins, we Germans who have been expelled still dream of returning, because no other land can replace it.

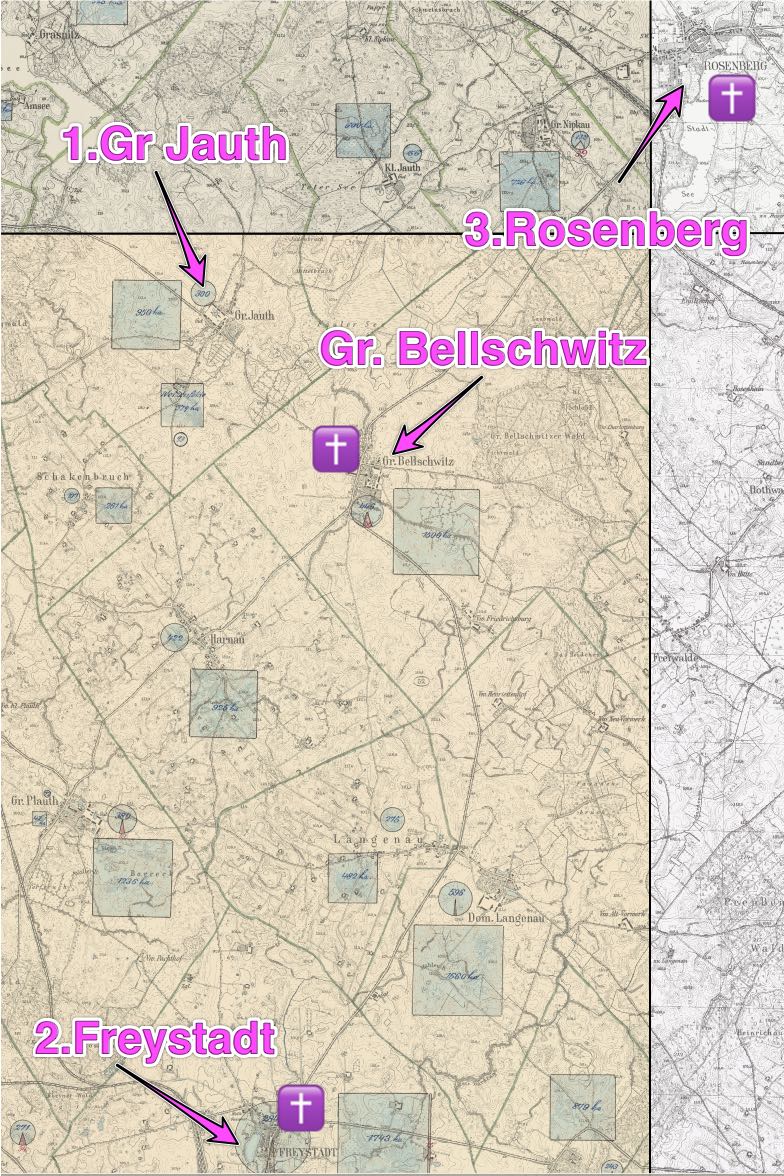

Via church records available on this site, I can trace my own paternal (Deutschendorf) family line, in reverse chronological order from Buffalo, NY, to Rosenberg, West Prussia (present-day Susz, Poland), then to a small satellite village southwest of Rosenberg called Groß Jauth which no longer exists and which, despite the deceptive name, was not large enough to merit its own church.

At that point the record trail ends. So I'm not able to directly connect my paternal line to the village of Deutschendorf explicitly via any records. But I assume that connection must have existed even if it's lost to history.

So were my Deutschendorf ancestors among those very first German settlers who founded the village of Deutschendorf? That is almost certainly an unanswerable question at this time. But given that our family name obviously stems from the town name, it seems we're as likely as anyone to have direct ancestral ties to the initial settlers.

I'm not sure exactly when the concept of the family name was established in Europe or East Prussia, but it seems like that must have taken place quite long ago. Apparently for my paternal line, it happend sometime after the early 14th Century when the village of Deutschendorf was founded.

In the recorded history of the church of another Prussian city, Rosenberg (see below), an (incomplete) historical list of the names of local clergy is given which indicates that family names were in use there by the early 16th century – at least by the clergy.

What follows is my description of the record trail from the earliest record of my direct Deutschendorf ancestors until their emigration to the US in 1871.

Deutschendorf Family Record Trail

In 1816 my 4th great-grandfather Michael Deutschendorf Sr was living in Groß Jauth, a small satellite village of the city of Rosenberg (about 1,200 residents then), which in turn was the capital of the surrounding »Kreis« (County) of Rosenberg, West Prussia.

Like most of the local inhabitants, the Deutschendorf family was of the Protestant confession. Groß Jauth was too small to warrant its own church, so they attended the Protestant church in the neighboring village of Groß Bellschwitz

Michael Sr was employed as a »Waldwart« (Forester). He was already married to my 4G Grandmother, Louise Krakau, and they had an adolescent son, Friedrich, (my 4G uncle) who may have already reached his teenage years.

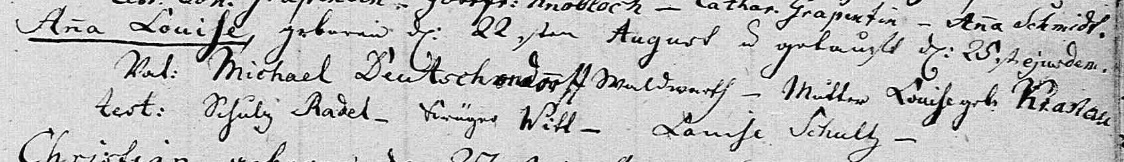

I know all of this information because in August of 1816, the very earliest direct reference I've found to my Deutschendorf ancestors appears in the church records of Groß Bellschwitz; Louise had just given birth to a daughter, Anna Louise Deutschendorf (my 4G aunt), who was baptized there.

TIP: You can view the entire baptism record yourself by visiting Anna Louise's page and scrolling down to the "Baptism" item in her timeline. I have English translations provided there as well as the original German. The same goes for any other record mentioned on this site – just navigate to the related person's page and look for the event and images/translations in their personal timeline.

Krakau Family Name

Let's briefly examine my 4G Grandmother's family name: Krakau.

Krakau is the german spelling of the Polish city of Krakow, and is pronounced the same way. Presumably, if Louise Krakau's paternal line could be traced back to the time when the concept of family names first became common (it can't), the family would be found to have lived in Krakow, Poland – which is relatively close to East Prussia.

By the early second millenium, Krakow was apparently the central capital city of the Polish people/nation. That would seem to indicate that Louise Krakau's paternal line was of Polish ethnicity rather than Germanic. That is absolutely possible, and probably even likely… but a German background may be more likely than it first seems.

First, the name Krakau is spelled in the German fashion… although that doesn't really prove much since the spelling could certainly have changed to the German version after her once-Polish paternal ancestors were Germanized in German East Prussia.

But second and more importantly, it seems there was significant German presence and influence in Krakow, even before the (late) middle ages. The following short passage comes from Manfred Raether's excellent book "Poland's German History", published in 2004.

Numerous cities with German dominance and German Law were founded in Polish regions between 1250 and 1300. German – specifically Magdeburger – Law was in effect in Krakow, Posen, Radom and Sandomir, among other cities. Additionally, a significant portion of the citizenry of these cities were ethnic Germans who held important positions, influencing the early city development as well as trade. Many Polish trade centers essentially developed into German-governed islands inside the Polish-controlled regions.

And further:

At this time [1477], Poland's capital and royal-seat Krakau was still in many ways a German-dominated metropolis – although by the end of the 15th century, an unmistakable Polonization of the German population had begun.

The German population of Krakau was roughly 75% in 1400, but by 1500 it had dropped to roughly 25%.

So whether Louise Krakau's paternal line was ethnically of Polish or German origin is hard to say.

Trail's End

The curious thing, and the barrier which I've so far been unable to overcome while researching my paternal line is the following:

Despite the church records of Groß Bellschwitz and all of the neighboring communities being surprisingly complete and available for easy searching online, record of Michael Deutschendorf Sr, his wife Louise Krakau, and their families does not appear earlier than 1816.

Michael Sr and Louise's birth records are nowhere to be found in this area, nor is record of their marriage, nor the birth of their first son Friedrich. Nor are there records of any other Deutschendorfs or Krakaus nearby who might qualify as extended family members.

In other words, it seems clear to me that Michael Sr and his small family (wife Louise and son Friedrich) had recently relocated to Groß Jauth from rather far away. And shortly after their arrival, they had a new baby girl, Anna Louise.

Napoleonic Wars?

The timing for this evident family relocation is interesting, to say the least. In 1816 the Napoleonic Wars had just come to an end with the Battle of Waterloo in present-day Belgium in June of 1815. Prussia and Prussian soldiers were directly involved in both.

This timing is especially relevant when combined with Michael Sr's occupation. Michael Sr's occupation as a »Waldwart« (Forester) is attested in four separate records, and his new home of Groß Jauth was indeed bordered by a forest. Additionally, his occupation is later attested in three further records as »Jäger«.

Translated literally, »Jäger« means "Hunter", and is familiar from the German liquor brand »Jägermeister« ("Master Hunter"). But »Jäger« was also a term used for a certain type of quasi-elite rifleman or sharpshooter/sniper in the German military of that time.

I found this tantalizing nuget on the German »Jäger« Wikipedia page under the "…in the Military" heading (emphasis mine):

After completing their military services, every member of a Jäger-Unit was entitled to a position as a Forester, which meant their future, in contrast to other infantry members, was secured.

So apparently, a »Jäger« was guaranteed to be provided a secure job as a Forester somewhere after retirement.

This seems a likely back-story for our Michael Sr, who:

- appears with his pregnant wife in a totally new town/region about a year after the Napoleonic Wars ended

- is employed as a Forester, but is also later referred to as a »Jäger«.

I don't think it's just wishful thinking on my part to assume that Michael Sr had likely served as a soldier in the Napoleonic Wars in a »Jäger«-Unit as a sort of sharpshooter!

The timing works: Michael Sr and Louise Krakau would have married and had their first child (my 4G uncle Friedrich) some time after the turn of the 19th century, before Michael left to serve in the military. As the war ended in summer of 1815, he could have relocated to receive his pension as Forester in Groß Jauth and promptly got his wife pregnant with (my 4G aunt) Anna Louise, born in August 1816.

Might Michael Sr have even been among the 50,000 Prussian solders who fought in the battle of Waterloo? It definitely seems possible! But to be fair, I have no evidence of that. It's certainly something I'd like to research further.

Missing Birthplaces

Even if all of those assumptions are true, it leaves open the question of where Michael Sr and Louise were born and married before the war. That information is essential for tracing my ancestry any further back.

Late-Breaking Update

Update: My recent research efforts have actually partially solved this mystery. I've traced Michael Sr & Louise back to the rather bustling port city of Elbing where they must have been married around January 1814 after having a daughter out of wedlock who died soon after.

This would mean that Mike's eldest son Friedrich (the Schuhmacher) must have been from a previous first wife, which makes sense given how young Louise would have to have been in order to continue to have children.

I strongly suspect Michael Sr was born in the tiny nearby costal village of FischersCampe in 1776, which allows me to trace my paternal Deutschendorf line a couple of generations farther back -- all in FischersCampe.

I haven't been able to find Louise's birth record, but there is a Krakau family in the area of FischersCampe (the triangulation of Deutschendorfs & Krakaus in the same small area is what led me to these discoveries in the first place).

I still haven't been able to find evidence of military service for Michael Sr, but I still suspect that occurred. More to come on these topics, but let's move forward in time…

Village Life in Groß Jauth

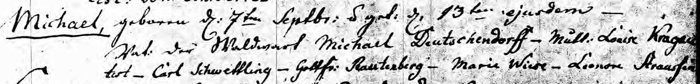

Regardless, two years later, in 1818, and still living in the small town of Groß Jauth, and still attending the local Protestant church in Groß Bellschwitz, Michael Sr's wife Louise gave birth to my 3G grandfather, Michael Deutschendorf Jr. Presumably, all was well with the Deutschendorf family.

But three years later, in 1821, disaster struck. Still living in Groß Jauth, Louise died from "complications of labor" after delivering her 4th child, (my 4G uncle) Wilhelm Deutschendorf. The child lived just long enough to be baptized, before also dying only days later.

Michael Sr still had three kids to raise, and apparently wasted no time finding a new wife; he married a widow named Helena Galleÿ née Budinski from the tiny nearby village of Schackenbruch just three months later in July 1821.

City Life in Freystadt and Rosenberg

In the following years, the Deutschendorf family must have relocated from the small village of Groß Jauth to the nearby city of Freystadt (there's a nice YouTube video with some historical images of Freystadt), because in 1828 Michael Sr's second wife Helena dies of "measels" in Freystadt and Michael Sr is mentioned in the burial record. Michael Jr would have been only 10 years old at that time, so presumably the entire family had transitioned somewhat from life in a tiny village to life in a small-ish city. Freystadt had about 1,100 inhabitants then.

Why did the family decide to trade village life for city life? I've found two possible hints:

- In the second volume of the "History of Rosenberg" (see below), the author casually mentions on page 103 that there was a fire in Groß Jauth in the year 1825. That would have been about the time when the family moved from Jauth to the city; maybe their moving was related to the fire.

- On page 152 of "The County Rosenberg: A West Prussian Homeland Book", it is explained that in 1829, a General Commission of the City of Freystadt determined that the local forestland had been over-utilized and decided to both confiscate the remaining woodlands (120 hectares) for preservation, as well as buy some adjacent farm land from private owners for re-forrestation. That sounds like an undertaking that might have required the employ of a local forrester or two. Maybe Michael Sr was involved. I don't know.

In 1831, three years after his second wife died, Michael Sr also died in Freystadt. The sickness indicated in his burial record is "Lung Infection". His youngest child, my 3G grandpa Michael Jr, would have been 13 years old. But by this time Michael Sr's oldest child, my 4G uncle Friedrich (the one born before the Napoleonic Wars), was already making a living as a (married) »Schumacher« (Shoe Maker) in the nearby city of Rosenberg.

Perhaps adolescent Michael Jr went to live with his older brother in Rosenberg, because from this point on, references to our Deutschendorf family appear exclusively in the (Protestant) Rosenberg church records.

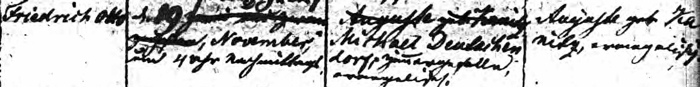

By the early 1840s, Michael Jr had reached young adulthood in Rosenberg, he was employed as a »Zimmergeselle« (Journeyman Carpenter), and he had married a widow with two children from her first marriage named Augustine Schilke née Kanitz.

Michael Jr and his wife Augustine had three children of their own before 1850: My 2G grandpa Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf, a girl named Bertha Auguste Deutschendorf who died at age four, and Eduard Robert Deutschendorf who grew up to be an »Ulan« (Mounted Policeman) in Rosenberg before he later also served as a »Gendarm« (Police Soldier) in the relatively far-away metropolis and capital city of East Prussia, Königsberg (modern-day Kaliningrad, Russia).

Kanitz Family Name

Other than the name and profession of her father Carl, a »Schmiedmeister« (Master Blacksmith!), I know very little about Augustine Kanitz's background or ancestry. But the Kanitz name itself might provide some clues.

Family and place names ending in "-itz" or "-witz" are known to be the Germanized version of a Slavic/Polish suffix "-vich," "-vic," or "-wicz" meaning "son of," "child of," "family of," "clan of," etc.

There also happened to be a relatively nearby town in the neighboring County of Marienwerder, West Prussia named Kanitzken. The -ken ending on German place names is cognate with the English word kin ,as in "family relation", and has roughly the same meaning as the -witz ending above. So the place name Kanitzken would (redundantly) indicate something like "the place where the Kanitzes live."

Indeed, I have the following evidence that Augustine Kanitz was probably born in Kanitzken before she (or her father?) moved to Rosenberg:

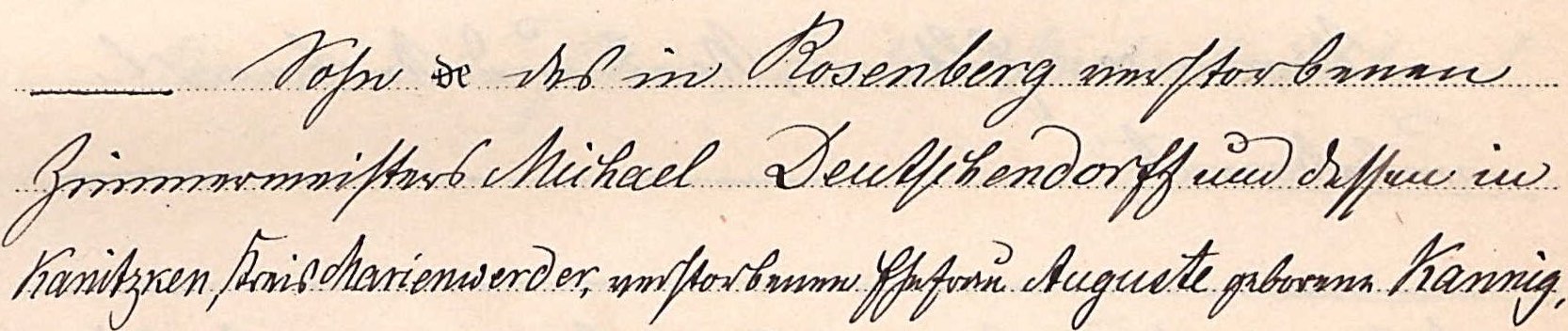

As briefly mentioned earlier, Michael Deutschendorf Jr and Augustine Kanitz's youngest child was my 3rd Great Uncle Eduard Robert Deutschendorf who grew up to be a police officier in far-away Königsberg, where he died in 1893 (after my direct Deutschendorf ancestors had already emigrated to America). His death record contains a tantalizing yet confusing hint about his mother, Augustine Kanitz's, origins. It says my Great Uncle Eduard Robert was:

Son of the Master Carpenter Michael Deutschendorf, who died in Rosenberg, and his wife Auguste née Kannig, who died in Kanitzken, Kreis Marienwerder.

This record appears to get a couple of details wrong, but I suspect it also provides clues to the truth. Keep in mind that this document was written rather far away in time and space from Augustine Kanitz's death, so it's not surprising that the recording official got some details wrong… he would have been an official in the metropolis of Königsberg East Prussia, and would have never before met or heard of the parents of the man whose death he was recording – Michael Deutschendorf and Augustine Kanitz, who were also deceased and who came from small towns in far-away West Prussia.

The official appears to get Augustine's last name slightly wrong: Kannig instead of the correct Kanitz. He also gets her place of death wrong. I know Augustine died in Rosenberg, not Kanitzken, because I have a very clear record of that which you can see at the bottom of Augustine's page.

But notice that this official mentions the far-away, tiny village of Kanitzken, Kreis Marienwerder very specifically. That's far too specific and unlikely to be a total mistake. It seems unlikely that many residents of Königsberg would even know of this tiny village. Therefore, I strongly suspect that some information was slightly mangled between this official and whoever was providing him with the family background information to be recorded in this document. I suspect Augustine Kanitz may have been born in, rather than died in, Kanitzken.

That suspicion led me to search for records of Augustine or her father Carl Kanitz in or around Kantizken in years prior. I presumed her birth record could be found there. It turns out that Kanitzken was another one of those villages that was so small that it didn't have a church of its own. The nearest Protestant church was in the neighboring town of Groß Nebrau. I scoured the church records of Groß Nebrau, but found no records of any Kantizes there at all.

Maybe Augustine was born into a Catholic family? That seems unlikely considering Augustine married two Protestant men (her first husband died before she re-marred my 3G Grandfather Michael Jr), and lived in Protestant-dominated areas, and the births of all of her children and her own death were all recorded in Protestant church records.

As for her ethnic background, I suspect that Augustine Kanitz's paternal line had probably been Polish, but that the family had long since been Germanized – they practiced the Protestant religion, they had traditionally German-sounding given names, and they spoke German (and probably didn't speak Polish anymore). Or perhaps her paternal line may have been Germanic, but I find that less likely.

The Carpenters

But back to Michael Jr (my 3G grandpa) and his son Friedrich Otto (my 2G grandpa) living in Rosenberg. Friedrich Otto was born in 1843 when Rosenberg had roughly 2,000 inhabitants, 95% of whom were Protestants.

Evidently, Michael Jr eventually graduated from Journeyman Carpenter to »Zimmermeister« (Master Carpenter) status – this occupation is attested in three separate church records referencing him.

Friedrich Otto apparently took after his dad. Three different documents list him as being a »Zimmerpolier«, which I've translated as "Foreman", and which was presumably associated with the other »Zimmer-« jobs, all relating to carpentry.

Wikipedia defines a »Zimmerpolier«:

A »Zimmerpolier« may be, depending on the division of tasks, either part of, or even leader of, an entire construction project. »Zimmerpolier« are in some cases responsible for additional tasks on the construction job, not just wood work. The employer assigns a »Zimmerpolier« to a construction project, who then leads and carries responsibility for the project.

A two-volume history of the city of Rosenberg written in 1937 by a man named Josef Kaufmann contains some general comments made about commerce in Rosenberg in its earlier history:

…thus the small city was primarily inhabited by those working in agriculture, there were no salesmen at all, only two small shopkeepers who traveled between the local »Jahrmärkte« (quarterly markets) selling their haberdashery (fabric goods needed for knitting and clothing). Among others, there were no: Coopers (barrel makers), Glaziers (window makers), Hat Makers, Rope Makers, Tanners, Woodturners, or Carpenters.

The second volume also lists historical details about various occupations performed in Rosenberg through the centuries. I was disappointed to find that there was no entry for "Carpentry" there, but then found this note at the end:

»Zimmerleute« (Carpentry): see above under »Mauerern« (Masonry).

So then under "Masonry":

It's impossible to be certain how old the masonry profession in Rosenberg is, because contracts/records are not available. But it is unavoidable that it must be one of the oldest occupations here.

… However, by 1851 there was not yet a local masonry business in Rosenberg, rather the single Mason employed in Rosenberg was a member of the masonry trade in the neighboring city of Riesenburg.

Not until the 3rd of September, 1863, did the Masons and Carpenters from Rosenberg, Freystadt, Deutsch Eylau and Bischofswerder (all neighboring cities) form their own local guild with its seat first in Freystadt, but then relocated to Rosenberg in December 1866.

By the year 1900, Rosenberg had 2 Master Carpenters and 2 Masons, but by 1910, only one of each.

So as Master Carpenter and Foreman respectively, Michael Jr and son Friedrich Otto may have each been one of no more than a small handful of such specialists in the 2,000-occupant city of Rosenberg of the 1840s-1860s. And it seems certain they must have been involved in the formation of the guild in Rosenberg mentioned above.

Friedrich Otto would later undertake the long journey to America, and there he is listed in four separate Buffalo, NY city directories (1872-1875) as a Carpenter.

The second volume of Kaufmann's history also mentions major repair and improvement projects to the Rosenberg church taking place from 1840-1847 (p160), and again in 1852 (p169). Although many details of the two projects are mentioned, those details do not include any names of the men involved in the actual construction work. Michael Jr was a »Zimmergeselle« (Journeyman Carpenter) living in Rosenberg during all of those years… might he have been involved in the work?

Über Rosenberg

In 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars and after France had subjugated Prussia, Napoleon himself took up residence near Rosenberg in the neighboring estate of Finkenstein for a time. Napoleon's doctor, Percy, thus had occasion to visit Rosenberg and wrote a description of the city in 1807 (shortly before my ancestors moved there):

He called Rosenberg a small, handsome city… "The residents are good people, and the atmosphere is pleasent. The old city offers a few charming features; the houses are clean and built with good taste. Before most of them stand cone-shaped Lime Trees, which look very handsome. The love of flowers is very evident here, a window which has not been decorated with Geraniums or Roses and such is nowhere to be seen. Yesterday I saw splendid bluming red Night Violets, Carnations, and Violas… I feel very at ease here. If only I could remain here for a month or so."

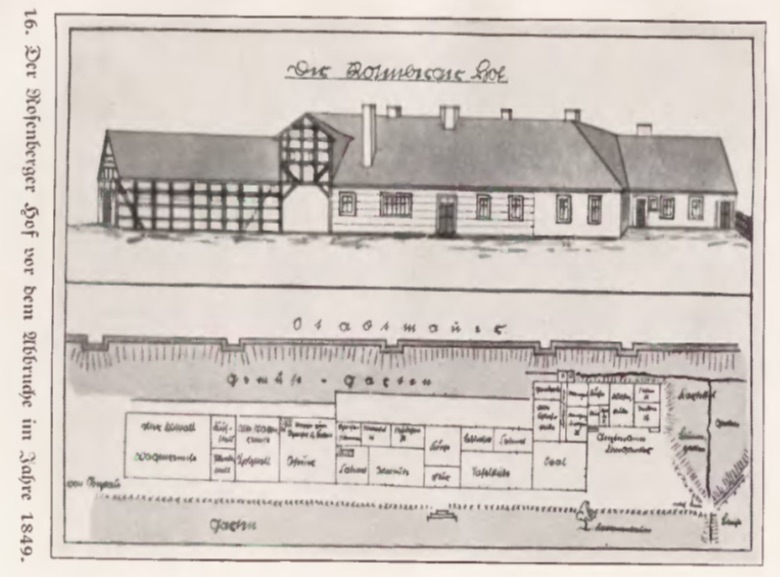

The Central Rosenberg Courtyard before it was torn down in 1849:

Eloped?

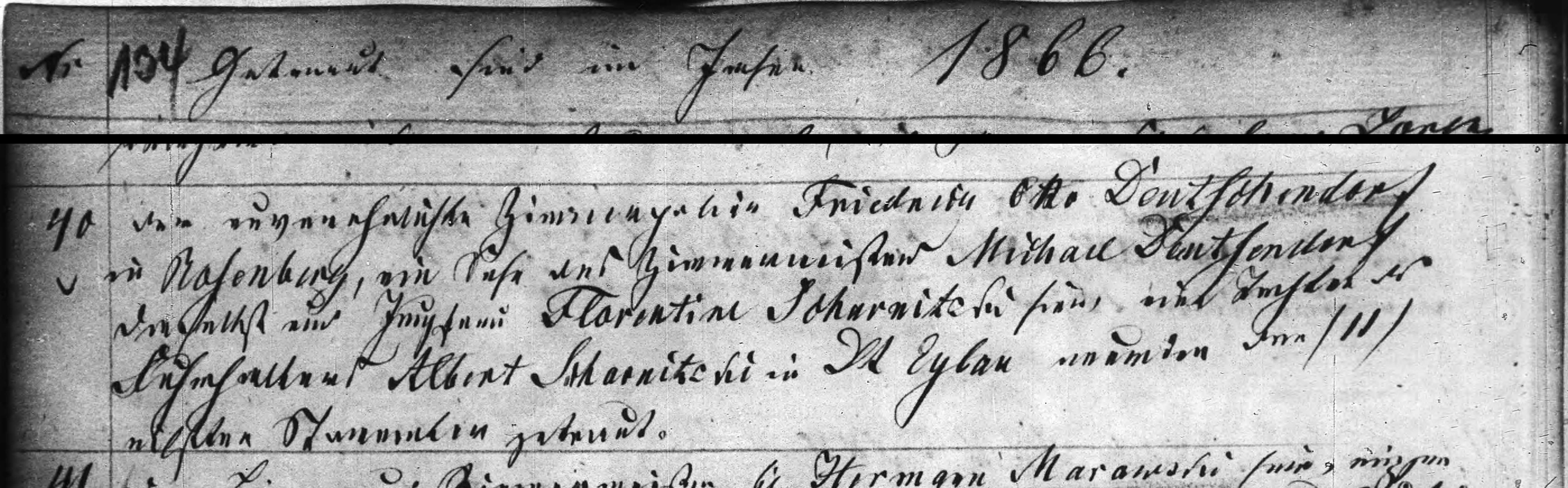

On 11 November 1866, Friedrich Otto (my 2G grandpa) married a young woman from Rosenberg named Florentine Friederike Caroline Czarnetzki (my 2G grandma). But their marriage is at least a little bit mysterious. Here's why.

In 1866, Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf was living in Rosenberg. Florentine Czarnetzki and her family were living in a slightly larger city which lies about 25 kilometers to the east called Deutsch Eylau. It was typical at that time for couples to be married in the bride's home town, and that pattern is evidenced in most of the marriage records I've found for my Prussian ancestors. So one would expect that Friedrich and Florentine would be married in the bride's family's current town of Deutsch Eylau.

Curiously, Friedrich and Florentine weren't married in either Deutsch Eylau or Rosenberg, but rather in the city of Marienwerder… a larger city about 30 kilometers due west of Rosenberg.

So not only did the couple's wedding not take place in the bride's town, it took place a good 50 kilometers away, on the far side of the groom's town, in the larger city of Marienwerder. Further, neither Friedrich nor Florentine seem to have any family connection to Marienwerder whatsoever.

There's one more bit of evidence that leads me to believe these two my have eloped, and it comes from the marriage record itself. Here's the record and my English translation:

The un-married Foreman from Rosenberg, Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf, son of the Master Carpenter Michael Deutschendorf and the virgin Florentine Scharnitzki, a daughter of the vassal Albert Scharnitzki in Deutch Eylau, were married on November 11.

The curious detail here is that Florentine's father's name is given as "Albert Scharnitzki", although I'm certain her father's name was actually Carl Ludwig Czarnetzki. The different spellings of the last name are inconsequential – that's thoroughly common for the time, and they're clearly meant to be the same name. The curious part is the first name, Albert.

I have ample and convincing evidence that Carl Ludwig was Florentine Czarnetzki's father's name, not Albert. In fact, there's not even any record of an Albert Czarnetzki living in Deutsch Eylau around that time who could be Florentine's father. Additionally, there's only one Florentine Czarnetzki from Deutsch Eylau at that time – and some later life events closely tie Florentine to her sister Amalie (also daughter of Carl Ludwig) Czarnetzki.

So why is the wrong name on the marriage record? A marriage record that stems from a large city far from the home of both the bride and the groom? Was eloping a concept at that time and place? Or perhaps the couple found themselves in Marienwerder for an extended stay related to Michael Jr's carpentry work, and the local clergyman made an error – he wouldn't have personally known any of the Czarnetzkis from relatively far-away Deutsch Eylau. Who knows.

Czarnetzki Family Name

Florentine Czarnetzki's father's ethnic background is obviously Polish, although it's virtually certain that they belonged to the Prussian Poles who had succumbed to Germanization one way or anther – they had probably long since traded the traditionally Polish Catholic faith for the traditionally German Protestant faith, and they certainly spoke German. And both Florentine's and her dad's given names were conspicuously German-sounding; her dad was named Carl Ludwig Czarnetzki. Perhaps they were over-compensating. Or perhaps not?

Kaufmann's history of Rosenberg notes that by 1785, there only remained a very small number of Polish-speaking inhabitants living at a single estate near Rosenberg (Groß Brausen), yet the Protestant Prussian clerical authorities would not allow the city of Rosenberg to phase out the Polish-language church service. That Polish church service entailed the expense of the salary for an extra polish-speaking pastor via public funding. The author expresses his belief that this is a sign of the "tolerance of the Prussian government", and it seems hard to disagree. However, by 1799, it was reported that even with several days' notice, literally no one would appear for the Polish services, so the practice was finally ended in Rosenberg as it had already ended in several nearby cities (p222).

Given this information, it seems that my Czarnetzki ancestors living in and around Rosenberg in the 1800s would have been thoroughly Germanized from a cultural perspective. Genetically speaking, they almost certainly carried Germanic blood as well as slavic after many generations of mixing. They surely spoke German (and almost certainly didn't speak Polish), and they probably considered themselves »Deutsche«, and as German as anyone else. This seems confirmed by the plethora of slavic-sounding names ending in -ski or -zki appearing in the local church books. Such slavic family names also appear frequently in a list of officials and persons in conspicuous leadership roles mentioned in Kaufmann's history of Rosenberg (a German-speaking Protestant city in a German-speaking Protestant region). This further indicates that many Poles were fully assimilated into the Germanic Prussian society by now. I gather these "Poles" would have considered themselves just as "German" as, say, a third-generation American "Lewandowski" would consider himself "American".

The Czar- in Czarnetzki is apparently related to the Polish word for black, so the name indicates dark hair and seems to be the Polish equivalent of the German name Schwartzkopf.

Unlike the Krakaus and the Kanitzes, I've been able to uncover a great deal of the Czarnetzki family history through local (Protestant) church records. Much like the Deutschendorfs, the Czarnetzki family has (even deeper) ties to a small satellite village of Rosenberg, in this case a town called Groß Plauth.

Emigration to the US

Anyhow, back to Rosenberg and the Deutschendorfs. My 2G grandpa Friederich Otto and his wife Florentine had three children in Rosenberg by the end of 1870:

- Bertha Auguste Deutschendorf, apparently named after her dad's sister who had died at age 4

- Mathilde Pauline Deutschendorf

- My great-grandfather, baptized Karl Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf

By summer of 1871, the time had come: the Deutschendorfs had obviously decided to emigrate to America, despite having 3 young children under the age of 5. The brief Franco-Prussian War had just come to an end in May 1871, which had hampered some German shipping lines from conducting their normal service for German emigrants to America.

Friedrich's dad, Michael Jr, had just died of "Stroke" in Rosenberg in 1870, so maybe that was also part of the reason they felt they could now make the big move. Although Friedrich's mom Augustine was still alive and certainly still living in Rosenberg (she died there in 1880 of an unspecified illness).

Another reason for the move may have been military reforms announced in conjunction with the »deutsche Reichsgrundung« (Formation of the German Reich) which had just occurred in January 1871. With few exceptions, most men would be obligated to fulfill 7 years of military service before reaching age 32. Friedrich was 27 years old at this time, and it seems unlikely from the records I have that he had yet performed any military service. I'm not certain whether he would have been affected by the new military requirements… although he may not have been certain either.

But more importantly, one of Florentine's sisters, Amalie, and her husband Friedrich Katoll had just relocated across the Atlantic to Buffalo, NY two years prior (before the war in 1869). Surely they had a major influence on our Friedrich and Florentine making the big move – and their ultimate destination was the same: Buffalo, NY. It seems likely these trans-atlantic relocations were coordinated in some manner.

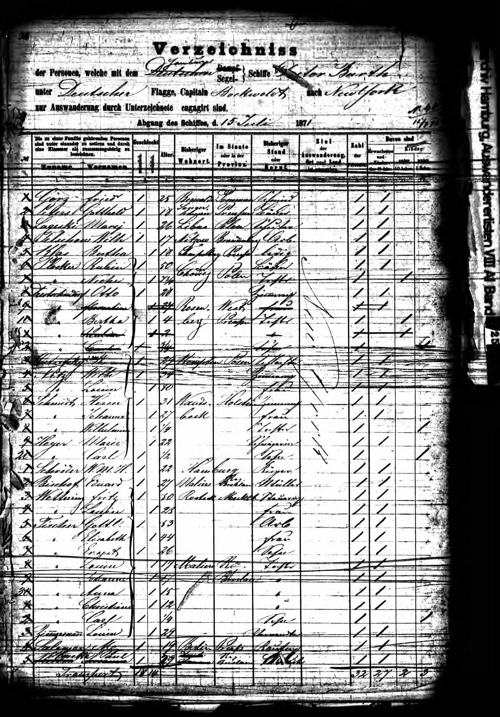

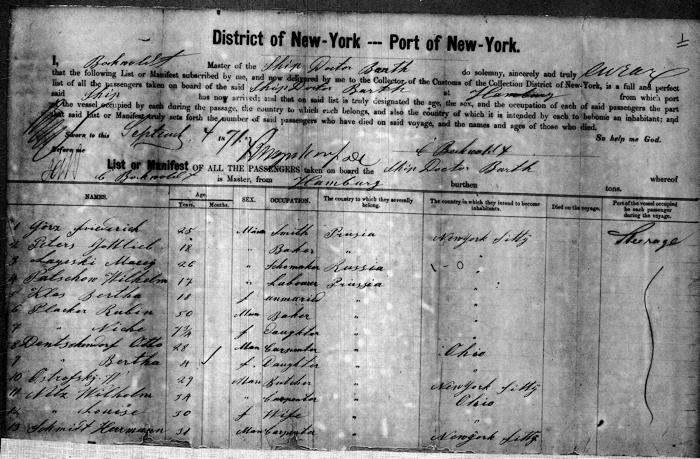

Somehow, the family made their way to Hamburg, Germany over 800 kilometers away, and booked passage via the Rob. M. Sloman Shipping Line – the oldest German shipping line – to America. Here's the Register for a boat called the Doctor Barth departing Hamburg on the 15th of July, 1871:

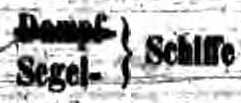

Interesting that it was a sail boat! »Dampf« (Steam) is crossed off on the doc, and »Segel« (Sail) is indicated next to »Schiffe« (Ship):

In fact, there's lots of info on this specific boat online. Here's a painting of it:

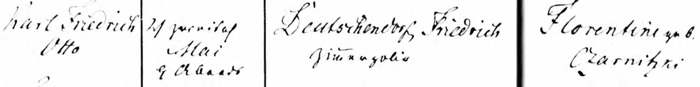

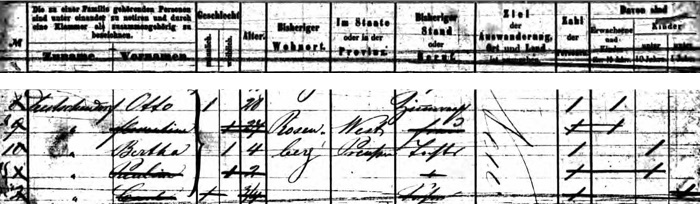

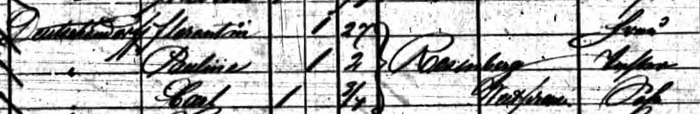

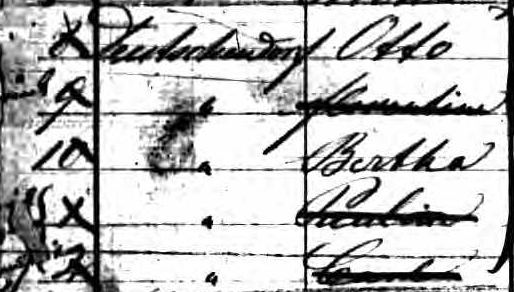

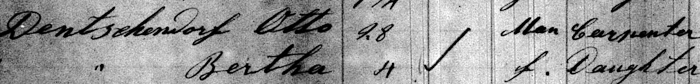

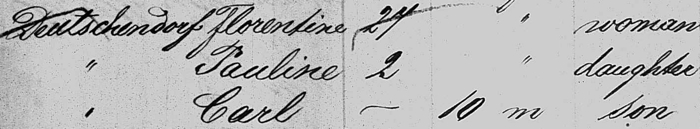

Here's our passengers of interest cropped along with the table headers:

In English:

| Persons belonging to a single family should be noted with a bracket. | Gender | Age | Former Residence |

In the State or in the Province |

Current Marital Status or Occupation |

Destination of the Emigration, Indicate Place and Country |

Number of Persons |

Adults and Children over 10 years |

Children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Last Name | First Name | M | F | under 10 years |

under 1 year |

||||||||

| Deutschendorf | Otto | 1 | 28 | »Zimmermann?« Carpenter |

1 | 1 | |||||||

| " | Rosen- | West | New York | ||||||||||

| " | Bertha | 1 | 4 | berg | Prussia | Daughter | 1 | 1 | |||||

| " | |||||||||||||

| " | |||||||||||||

It looks like Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf, age 28, of Rosenberg West Prussia, along with his wife Florentine Friederike Caroline (née Czarnetzki), age 27, and their three children:

- "Bertha" (Bertha Auguste) – 4 years old

- "Pauline" (Mathilde Pauline) – 2 years old

- "Carl" (Karl Friedrich Otto) – "3/4" years old

were set to depart on board. Some surprises:

- Our Friedrich is listed here only by his middle name "Otto", which made this harder to find.

- Karl is listed as "Carl", also causing confusion.

- But most interestingly, it looks like mother Florentine along with baby Pauline and infant Carl were crossed off the passenger list at the last minute! What could have happened?? Sick infant? Sick momma?

Further documents confirm that the mother, toddler and infant – for some reason – didn't leave on the same boat with father and daughter.

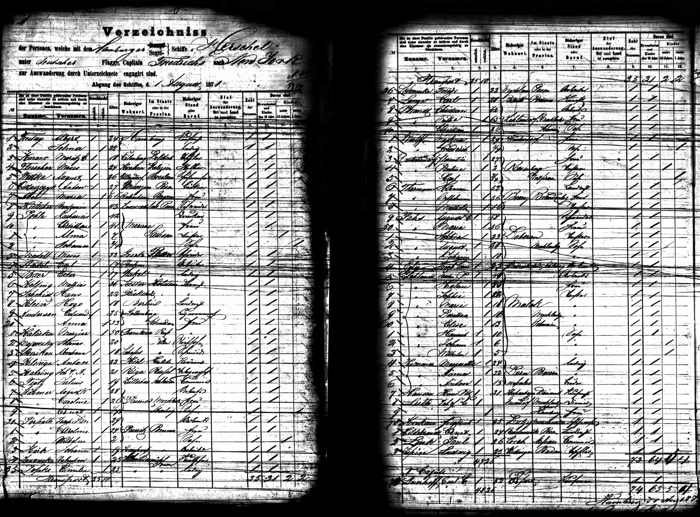

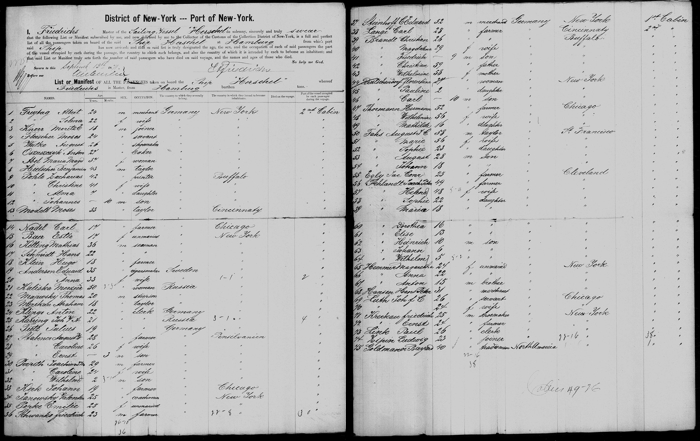

Specifically, a separate German Departure document from a separate sailboat – the Herschel – departing Hamburg two weeks later on Aug 1st, 1871:

Florentine, Pauline and "Carl" are on board, with given names and notes identical to the first register:

The two groups arrive separately in NY on their respective ships in the expected order. The first boat arrives (51 days later!) on Sept 4th, 1871:

"Carptenter" "Otto" and daughter Bertha are on board alone:

9 days later, on Sept 13th, 1871, the second boat arrives in NY:

Florentine, Pauline, and "10-month-old" "Carl" are on board:

Disaster Strikes (Twice) in America

So in the late summer of 1871 Friedrich Otto Deutschendorf, his wife Florentine, and their three children had arrived in America and they were headed for Buffalo to rendezvous with Florentine's sister and her husband, the Katolls. Presumably, they were filled with hope for their new lives in the Land of Opportunity. Tragically, their lives in the New World would not proceed as planned. In less than five years both Friedrich and his wife would be dead, and the three children would be living in a Buffalo orphanage.

What happened?

Sadly, it seems that Friedrich's wife Florentine must have died very soon after arriving in the US. In fact, I suspect that the same illness that prevented her from departing Hamburg on time may have caused her death immediately after reaching the US. Unfortunately, I don't have any records referencing Florentine or her death in America, but subsequent facts relayed below indicate this must be true.

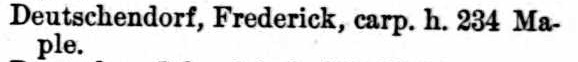

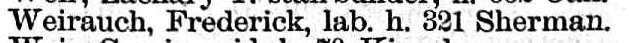

With or without his wife, Friedrich and his family made their way to Buffalo NY where his in-laws, the Katolls, were living. I know that because there are four Buffalo city directory entries from 1872-1875 referencing a Carpenter by the same name:

| 1872 | |

|---|---|

| 1873 | |

| 1874 | |

| 1875 |

I have also confirmed that there are no such entries in the Buffalo city directory for a Friedrich Deutschendorf in the surrounding years of 1871 and 1876 – strong evidence that this is our Friedrich.

Note the addresses listed above, particularly the last two:

| 321 German |

| 331 Sherman |

Despite the minor difference, I suspect these two address were meant to be the same: 321 Sherman. The "German" address is probably a typo. Either that or the typesetter was making a pun, poking fun at Friedrich's conspicuously German-sounding last name. This address on Sherman will provide important evidence later.

There are also Buffalo city directory records for Friedrich's in-laws, the Katolls, from 1872 and 1873. Further evidence that the move across the Atlantic was somehow coordinated between the two families: the Katolls also lived in the 200-block of Maple street. The two families were practically next-door neighbors when they arrived in America.

| 1872 | |

|---|---|

| 1873 |

After his wife's untimely death, Friedrich – just like his great-grandad Michael Sr – still had three young children to raise, so he quickly re-married. Via reports from other (distantly-related) family researchers on Ancestry.com, I gather Friedrich quickly re-married a woman named Louise Fischer in 1872. I don't (yet) have access to any contemporary records proving this, but it seems certain. Louise was apparently herself a child of German immigrants – perhaps brought by her parents to America in adolescence.

By 1875 Friedrich and his new wife Louise Fischer had two more children: Wilhelmina Deutschendorf, born in early 1873, and Julius Deutschendorf, who apparently died of drowning some time before reaching adulthood.

Young Wilhelmina went on to marry and have twelve children in Minnesota where many of her ancestors live today.

The Last Deutschendorf

On 7 October 1875, at the age of only 32, Friedrich himself died, leaving behind five children. Apparently, Friedrich the carpenter was working as a Steeplejack on a construction job at a church in nearby Elmira, NY. He fell to his death.

Although I have not seen it myself, according to this website, Friedrich's death is recorded in the ledger of the Woodlawn Cemetery in Elmira, NY.

This would have left my 2G Step-Grandmother Louise Deutschendorf née Fischer with three step children (Bertha Auguste, Mathilde Pauline and my great-granddad Karl) along with two children of her own (Wilhelmina and Julius).

By 1877 Louise re-married to yet another German man named Friederich – Fred Weirauch. Again, I have no records of this, but it is claimed by the Minnesotan Ancestry.com researchers, and I also noticed the following fact. In the 1877 Buffalo city directory, one Fred Weirauch is listed as living at 321 Sherman – the same address Friederich Deutschendorf lived with his second wife Louise Fischer. Apparently Louise inherited the house when Friederich Deutschendorf died, and when she re-married Fred Weirauch, they stayed in the house for some time. I gather they eventually moved to Minnesota.

| 1877 |

|---|

However, five children – including three step-children – was apparently too much for either Louise or her new husband Fred, or perhaps both. And there's more bad news. Florentine's sister Amalie Katoll had also died since arriving in America. I know this because her husband had remarried by 1875. Thus my 4-year-old great grandfather Karl and his two older sisters found themselves stranded on a foreign continent with not a single living adult blood relative. What would become of them?

Orphans

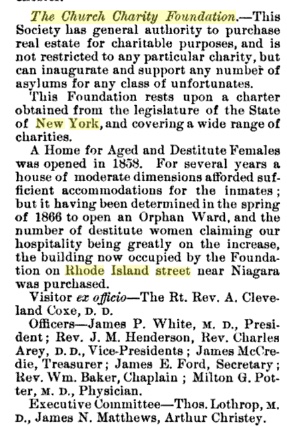

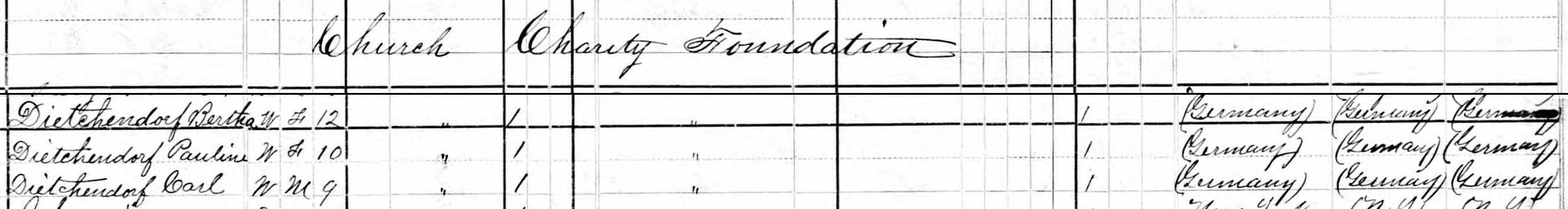

Apparently, they were deposited at a local shelter. The three children appear in the 1880 US Census as residents of the Orphan Ward of the nearby Church Charity Foundation, an institution of the Protestant Episcopal Church of Buffalo on "Rhode Island Street, near Niagara."

The 1880 US Census:

Name Change

All three children are listed as born in Germany. Note that their last names (Deutschendorf) have been misspelled as Dietchendorf. Unsurprisingly, with both of their parents dead, there was confusion about the proper spelling and pronunciation of their difficult German name.

The spelling seen here obviously would have been invented by an English-speaking American, and indicates that the name was then pronounced not with an »eu« OY sound as Deutschendorf is pronounced in present-day »Hochdeutsch« (High German), nor as a long EE sound as »ie« would be in modern High German, but rather as a long EYE sound as in English die or dye.

In fact, it's virtually certain that Deutschendorf was pronounced with a long EYE sound by my great grandfather and his family. Here's why. According to a German book published in 2014 by one Hermann Pölking, "East Prussia: Biography of a Province", the East Prussian German dialects were known for shifting the German »eu« OY sound into a German »ai« EYE sound. And the book specifically recounts that German »Deutsch« was pronounced »Daitsch« with a long EYE sound by East Prussians. To spell that East Prussian pronunciation phonetically in English, one would most likely use Dietch as in the english verb to die, as in to pass away.

Coincidentally, there are apparently some modern-day Austrian regional dialects of German where this identical sound change has occurred and still exists. I noticed that Austria's former Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache, who was born in Vienna in 1969, also pronounces the German word »Deutschland« (Germany) with a long EYE sound. This modern Austrian sound change is completely independent of the 19th century East Prussian sound change, but proves that such a sound change is not at all unlikely – it's occurred at least twice independently. Embedded below is a tiny clip of him saying »Deutschland« as »Daitschland« in 2019 [source].

This Dietchendorf spelling is seen in several subsequent records relating to my great grandfather, before my family name reached its current and final anglicized form, Ditchendorf with a short IH sound as in the english word ditch (as in trench). The switch to the short IH sound in english seems natural in hindsight, since English ditch is a very common word, but dietch with a long EYE sound doesn't closely match any English words.

There are apparently several Deutschendorf clans in present-day America, and although I suspect I am very distantly related to all of them, all of the living ancestors of my Friedrich Deutschendorf now carry the streamlined, anglicized name Ditchendorf.